Introduction

Meaning can be a sticky mess—much like trying to frost a cupcake with a brain. But fear not! In philosophy, we slice through the gooey mix with two tasty tools: intension and extension. This article unfolds these concepts in bite-sized, witty morsels, all backed by scholarly thought (no Wikipedia crumbs here).

What Are Intension and Extension?

- Intension refers to the concept or the “sense” of an expression—its internal recipe. For example, the intension of “bachelor” is “an unmarried adult male.”

- Extension is the set of all things in the world that fit that recipe—the “denotation.” So the extension of “bachelor” is {John, Marcus, Linda’s brother, …}

Frege’s Groundbreaking Recipe (1892)

Gottlob Frege introduced Sinn (sense/intension) and Bedeutung (reference/extension), showing that knowing an expression’s sense is not the same as knowing its reference. “The Morning Star” and “the Evening Star” share reference (Venus) but have different sense (Frege, 1892).

Carnap’s Semantic Seasoning (1947)

Rudolf Carnap formalized intension and extension in Meaning and Necessity (1947), using possible-worlds semantics. An expression’s extension can vary across worlds, but its intension remains the rule linking worlds to extensions (Carnap, 1947).

Montague’s Universal Oven (1974)

Richard Montague applied formal logic to natural language, treating intensions as functions from possible worlds to extensions (Montague, 1974). This turned philosophical frosting into rigorous syntax and semantics.

Philosophical Implications: Beyond Frosting and Sprinkles

- Necessary vs. Contingent: Intensions capture necessity (true in all worlds), whereas extensions can differ by world.

- Identity Puzzles: If two expressions have the same extension in the actual world but different intensions, substituting one for the other can change truth—a brain-twister shampoo for thought.

- AI & Linguistics: Modern AI models juggle intensions (concept embeddings) and extensions (token occurrences) when parsing and generating language.

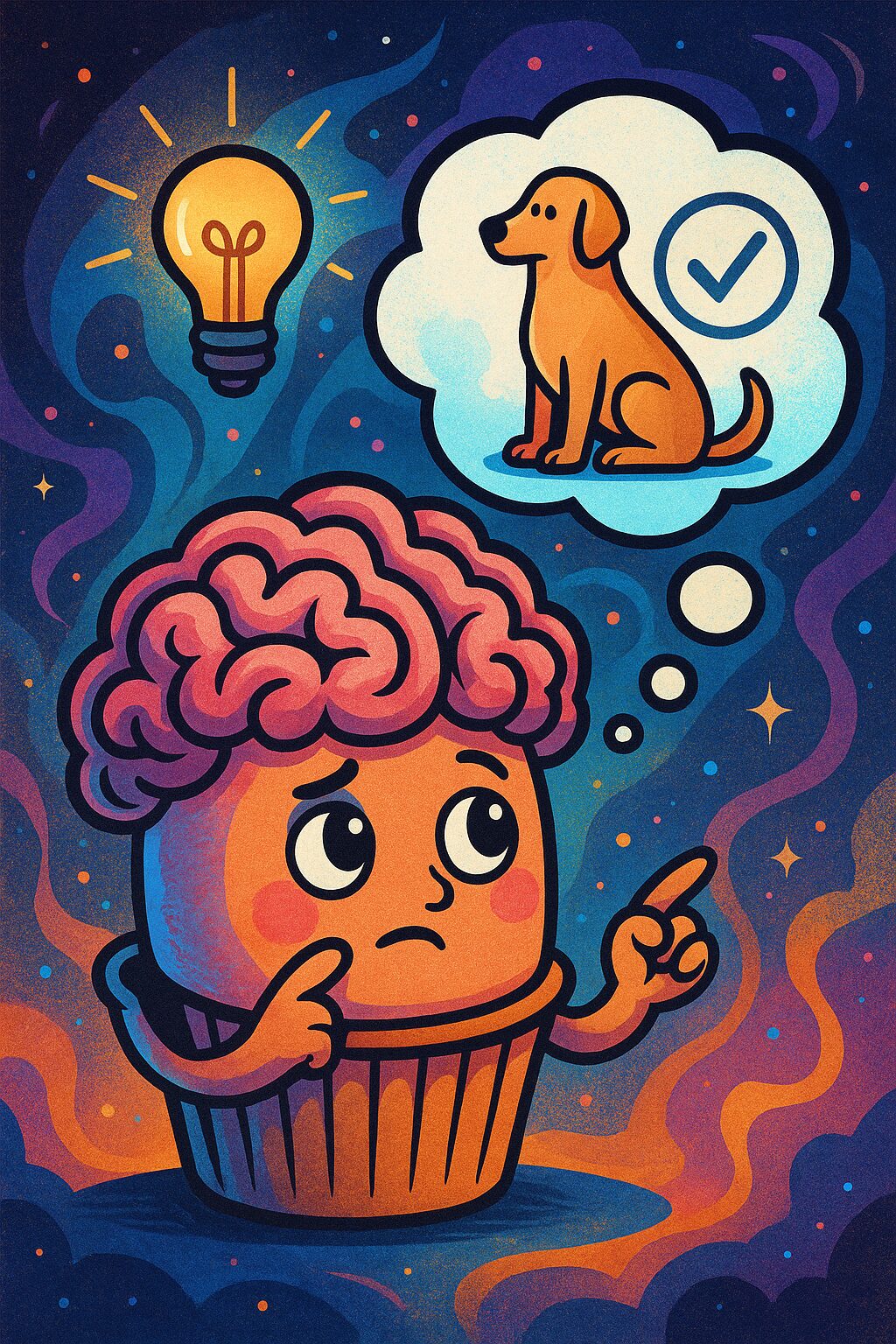

A Dash of Satire

Imagine a cupcake arguing with a dog about meaning. The cupcake insists on the intension of “good boy,” while the dog wags tail, nodding at every pup in the extension. Who wins? If you answer “both,” congratulations—you’ve grasped the philosophical swirl!

References

- Frege, G. (1892). On Sense and Reference. Zeitschrift für Philosophie und philosophische Kritik.

- Carnap, R. (1947). Meaning and Necessity: A Study in Semantics and Modal Logic. University of Chicago Press.

- Montague, R. (1974). Formal Philosophy: Selected Papers of Richard Montague. Yale University Press.

Disclaimer: This article was generated with AI.